October 1918

It’s been one hundred years since Captain Mitchell earned his Victoria Cross. One of the major roles of the military engineers is to provide mobility to their forces. This includes the construction of bridges and roads. During the night of 8/9 October, Captain Mitchell and a small group captured bridge, which had been set for demolition by the Germans. For this action, he was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC).

October 2018

As the calendar ticks toward 100th anniversary of the end of the Great War, articles are appearing on various activities during those last days of the war. Amongst those articles are several noting Captain Mitchell’s’ activities.

From The Torch, the newsletter of the Friends of the Canadian War Museum, this article.

Captain C.N. Mitchell –Victoria Cross By: Ed Storey

Born in Winnipeg, Manitoba on 11 December 1889, Coulson Norman Mitchell graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1912 with a degree in engineering. He enlisted in the Canadian Engineers as a Sapper on 10 November 1914, and later transferred to the Canadian Overseas Railway Construction Corps. He sailed to Britain in June 1915 and served briefly with his unit in Belgium from August to October.

Back in Britain, Mitchell was promoted to Sergeant in November and commissioned as a Lieutenant in April 1916. He was transferred to the 1st Canadian Tunnelling Company and served in Belgium in tunnelling operations, where he was awarded the Military Cross for his bravery in continuing to lay mines while cut off from his own lines. Mitchell was promoted to Captain in May 1917.

In the summer of 1918, Capt Mitchell’s unit was broken up and its soldiers sent to newly-formed divisional engineer battalions. Mitchell was posted to the 4th Battalion and went on to participate in the major battles of the Canadian Corps.

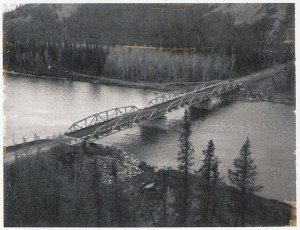

Captain Mitchell earned his Victoria Cross on the night of 8 to 9 October 1918 while leading a party of sappers on a reconnaissance mission near Cambrai in France. Their task was to venture beyond the Canadian front line to examine bridges over which the Canadian 5th Infantry Brigade proposed to advance, and to prevent their demolition. After finding

one bridge destroyed, Mitchell moved on to the next, which spanned the Canal de l’Escaut. Running across the bridge in total darkness, Mitchell found that it had indeed been prepared for demolition. With a non-commissioned officer he cut the detonation wires and began to remove the explosive charges. When the Germans realized what was happening, they charged toward the bridge but were held off by Mitchell’s sappers until reinforcements arrived. Saving the bridge over the Canal de l’Escaut contributed significantly to the later success of the 5th Infantry Brigade’s offensive operations.

Mitchell returned to Canada in 1919, resumed his civilian engineering career and served briefly in a militia engineer unit. In 1936 he was one of thousands of Canadian pilgrims

to attend the unveiling of the Canadian memorial at Vimy Ridge. While in France he returned to the bridges where he had earned his VC.

During the Second World War, he served in Britain in command of engineer units. In 1943 he returned to Canada as a Lieutenant-Colonel to command an engineer training centre. He left the army in 1946 and returned to his pre-war job with Power Corporation and lived in Montréal, until he retired in 1957.

LCol C.N. Mitchell, VC, MC died in Montreal, Quebec on 17 November 1978, and is the only Canadian Military Engineer to earn the Victoria Cross.

Citations

Lt. Coulson Norman Mitchell, Can Engrs

“For conspicuous gallantry in action. He displayed great courage and skill in countermining against enemy galleries. On one occasion he was cut off from our own lines for twelve hours. He has previously done fine work.”

(London Gazette, no. 1546, 13 February 1917)

Capt. Coulson Norman Mitchell, M.C. 4th Bn, Can Engrs

“For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty on the night of 8th-9th October, 1918, at the Canal de L’Escaut, north-east of Cambrai. He led a small party ahead of the first wave of infantry in order to examine the various bridges on the line of approach and, if possible, to prevent their demolition. On reaching the canal he found the bridge already blown up. Under a heavy barrage he crossed to the next bridge, where he cut a number of ‘lead’ wires. Then in total darkness, and unaware of the position or strength of the enemy at the bridgehead, he dashed across the main bridge over the canal. This bridge was found to be heavily charged for demolition, and whilst Capt. Mitchell, assisted by his N.C.O., was cutting the wires, the enemy attempted to rush the bridge in order to blow the charges, whereupon he at once dashed to the assistance of his sentry, who had been wounded, killed three of the enemy, captured 12, and maintained the bridgehead until reinforced. Then under heavy fire he continued his task of cutting wires and removing charges, which he well knew might at any moment have been fired by the enemy. It was entirely due to his valour and decisive action that this important bridge across the canal was saved from destruction.”

(London Gazette, no.31155, 31 January 1919)

From the Library and Archives Canada Blog – https://thediscoverblog.com/2018/10/08/captain-coulson-norman-mitchell-vc/ a write up on Mitchell. Also included are links to his service file and citations.

A couple of recently published books also briefly mention Mitchell’s actions.

The Selected Papers of Sir Arthur Currie, Diaries, Letters and Report to the Ministry, 1917 – 1933. published 2008, edited by Mark Osborne Humphries. Page 123

Reluctant Warriors: Canadian Conscripts and the Great War, published 2017, Patrick M. Dennis. Pages 165 – 166

Recent Comments